|

COVER STORY, APRIL 2009

BUILDING MORE FOR LESS

Low construction prices create opportunity for developers.

Jon Ross

Kenneth Simonson, chief economist at Arlington, Va.-based The Associated General Contractors of America, refers to Sept. 15, 2008, as “the day the music died.” Lehman Brothers was sounding its death knell. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had just gone into conservatorship. Those events, coupled with growing uncertainty about the residential housing market and the near collapse of lending, spelled hard times for developers in need of construction loans.

“Developers went to their once-friendly banks with either a new loan or a broad existing construction loan and found the credit window slammed shut on their fingers,” Simonson says.

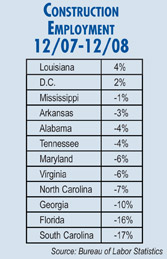

In the ensuing 6 months, commercial construction across the nation has all but stopped. Construction employment from December 2007 to December 2008 fell 8.5 percent, according to Simonson. The numbers in South Carolina and Florida are high marks in the Southeast, topping a 17 percent and 15 percent reduction, respectively. On the bright side, as construction unemployment rose, the cost of construction materials has fallen drastically. Available labor and cheap materials created the perfect chance for opportunistic developers to get projects off the ground.

“Material costs are down for the first time in 6 or 7 years. There are lots of skilled contractors eager to perform; labor is plentiful,” Simonson says. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices fell in January for aluminum mill shapes, asphalt paving mixtures, steel mill products, copper and brass mill shapes and diesel fuel. Simonson’s message to developers: break ground now before prices start rising. Concrete, gypsum and plastic construction products all increased in price in January. “A year from now, we could see material prices shooting up again, and sadly, some of the best qualified contractors might be out of business,” he says. “This is a limited time offer.”

At Owen-Ames-Kimball’s Fort Myers, Florida, office, construction activity is minimal. President David Dale estimates that more than $90 million worth of projects have been scratched in the past 16 months. “We haven’t experienced a weakness in commercial construction to this level before in this area, and we’ve been here since 1982,” he says.

He started seeing labor prices start to fall 18 months ago, and materials started to get cheaper 9 months ago, but so far, this price drop has generated little business. “Customers who know enough to take advantage of the extremely low prices and have the ability to do so are jumping in the market if they have the need,” he says. In Florida, not many of Dale’s clients have the need.

Developers would be taking advantage of the current situation if they could afford to break ground on new properties, Atlanta-based Hardin Construction’s Brantley Barrow says. But low material costs aren’t enough to fuel a resurgence in development. The lack of commercial lending, the recession and a general hesitation about new construction have turned active developers into wallflowers.

“Even though construction pricing has declined, so have the rents and income of our clients, which makes it that much harder for them to justify new development,” Barrow says. “The capital markets are demanding higher capitalization rates, while lenders are requiring higher loan-to-value ratios and interest costs on their loans. All of this is preventing many clients from taking advantage of the lower prices.” Simonson echoes Barrow’s sentiments, saying that even with the enticement of cheap materials and labor, developments are still stalled. “I can’t say I’ve seen any evidence yet that people are going ahead and starting projects,” Simonson says.

While university and hospital developers were navigating the beginning of the recession admirably, projects in those sectors have stopped as well. Endowments have taken a beating from Wall Street, and those with master-planned developments are now shrinking their outlook. At Hardin, Barrow started preparing for the downturn in 2007 by broadening the company’s geographic focus and pursuing more institutional assignments. Liquidity didn’t start evaporating until 2008, but it was this early preparation that has allowed Hardin to competently navigate the downturn. “Our volume will be down in most commercial markets this year, but we are obtaining more institutional work to fill the holes,” Barrow says. These projects include Georgia Southern University’s Centennial Place Student Housing complex in Statesboro, Georgia, and the Performing and Visual Arts Complex at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia. Barrow expresses hopeful optimism about the construction outlook. “Well-capitalized developers will be able to get ahead of the curve by buying construction services before the market starts to turn up and complete their projects as the demand and property values increase,” he says.

A few clients might simply be waiting for construction prices to hit bottom, though everyone agrees that costs are quickly approaching the cellar. “It’s hard to know where the bottom is, but I think we’re near the bottom,” Simonson says. Barrow’s advice to developers is to start working the second the market starts to regain ground. “The best time to start is at the first signs of recovery, so the developers can take advantage of lower pricing and be under construction as soon as the market starts to return, ” he says.

Simonson, Barrow and Dale heap most of the blame for the construction slowdown on the global financial crisis. A speculative free-for-all may also have had something to do with the current situation. Looking for someone to blame, Dale emphasizes that the lending markets shouldn’t shoulder the entire burden of fueling the recession. The largest obstacle to developers once again starting constructing projects? Consumer uncertainty.

“Fear seems to be the bigger factor,” he says.

CONTRACTOR HELPS REVITALIZE FORECLOSURES

Workouts provide opportunities for builders in down market.

By now, it’s become a familiar tune: a developer breaks ground on a project, construction money dries up and the lender forecloses. All across the country, when a commercial property enters foreclosure, lenders have traditionally sought to monetize the asset, sell it off and move on. The recession led to an outcropping of brokers offering valuation services for just this purpose. Affixing a price tag to a half-finished asset isn’t always the solution, says Ted Benning, III, of Atlanta-based Benning Construction. For the last year, he’s been guiding lenders through the ins and outs of property management. So far, Benning has handled a variety of property types, but most of his business focuses on for-lease buildings like retail and office space. Retail centers are at the top of the list.

“The numbers of foreclosures that the banks are dealing with right now are staggering,” Benning says. “Their workout departments are fairly small, and banks are not used to owning property.”

The workout step is where he comes in, offering lenders a solution to their property problems. Many of the foreclosed assets are incomplete shells of buildings, so he works with the lender to prevent their asset from further depreciating in value. The next step is mapping out a plan to get the property in working order. Additional difficulties arise in getting a building up to code and complying with environmental regulations.

Benning says his goal is different than the valuation divisions founded by brokers. “We’re not looking at the property from an investment point of view. We’re looking at the property in terms of maintaining value and how do we help the bank do that,” he says. “How do we take that asset and return it to a profit-making investment? How do we dress up this ugly, half-finished piece of a deal and make it look attractive?”

A key notion of this process is to not immediately try to sell the property, an idea that’s against the instinct of most lenders. “The right thing to do may be to stabilize until the market returns. Hang on to the asset for a year,” Benning says. “To do that, they’ve got to get into the property management business. They’ve got to start thinking a little bit more like a developer.”

Due to the sheer number of foreclosed properties and the limited workout capabilities of banks, Benning says he’ll be helping out with foreclosed properties for a while. He predicts the work won’t slow down for another 3 to 5 years. “As long as the banks have this book of assets they’ve foreclosed on, it’s a long-term deal,” he says. “There’s a lot to digest out there.”

— Jon Ross |

©2009 France Publications, Inc. Duplication

or reproduction of this article not permitted without authorization

from France Publications, Inc. For information on reprints

of this article contact Barbara

Sherer at (630) 554-6054.

|