|

COVER STORY, AUGUST 2012

CMBS REMAINS VITAL

Conduit lenders fill a need balance-sheet lenders often can’t.

Matt Valley

Although it will take at least a few more years for the commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) market to fully recover from the effects of a severe recession and lax lending practices that dealt it a major blow, securitized financing remains a critically important option for borrowers, say industry experts.

CMBS finance covers a broad swath of the market. Conduit lenders not only do deals with big-time borrowers that own trophy assets in major cities, but they also fill a void by providing capital to small and medium-sized borrowers that own Class B and C properties in secondary and tertiary markets.

“If you talk to any of the insurance companies, they will say that they primarily focus on the major urban areas with the exception of perhaps grocery-anchored retail. CMBS isn’t as picky,” says Tom Fink, senior vice president and managing director at New York-based Trepp, a real estate analytics firm. Fink has been involved in the securities market for three decades.

For every high-profile CMBS deal — like the $3 billion in CMBS debt placed on the Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Village apartments in Manhattan during the frothy lending period of 2005 to 2007 — there are hundreds of smaller CMBS deals originated monthly across the country.

For example, Johnson Capital and CRCapital Advisors arranged a $10 million CMBS loan for the 111-room Dauphine Orleans Hotel in the French Quarter of New Orleans this spring. The borrower, a local developer, used the proceeds of the loan to pay off existing recourse bank debt. The loan has a 10-year term with a 25-year amortization and fixed interest rate in the mid-5 percent range; it closed at 70 percent loan-to-value.

In a much larger transaction, Aries Capital announced in March that it arranged a $57 million CMBS loan for three Gulf Coast hotels: a Hilton Garden Inn and Holiday Inn Express in Orange Beach, Alabama, and a Hampton Inn in Pensacola Beach, Florida. All three Gulf-front properties are owned by Innisfree Hotels. The 10-year loan was used to refinance existing debt and fund seasonal reserves.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010 resulted in immediate hotel occupancy declines due to the perception that the area was tainted by the spill, and Gulf Coast hotels have found it a challenge to secure financing in the wake of the oil spill and its disruption on businesses in the area. CMBS loans are an important option for owners of properties facing challenges.

As for Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Village, the $3 billion CMBS loan granted to Tishman Speyer Properties and a unit of BlackRock Inc. was ultimately transferred to a special servicer in November 2009. In January 2010, the partnership announced that it was defaulting on the loan and turned the keys over to the creditors.

Turning the Corner

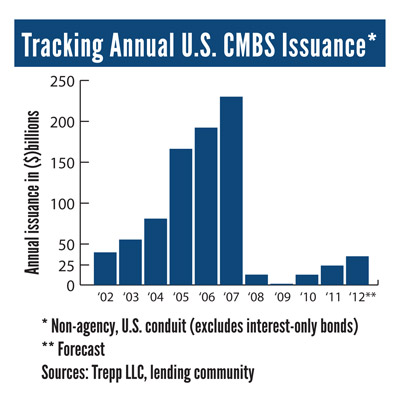

Total U.S. CMBS issuance this year is expected to range between $30 billion and $35 billion, up more than 20 percent from the $23.7 billion in issuance notched in 2011. Still, that pales in comparison to the $230 billion in domestic issuance recorded in 2007, the height of frothiness in the lending arena when excessive loan-to-values and declining debt-service coverage ratios were commonplace.

The subsequent meltdown on Wall Street in the fall of 2008 coupled with the recession put the CMBS market in a deep freeze for a few years.

“We need the CMBS market to generate $60 billion to $70 billion a year in capacity,” says Fink. “To that extent, we’re not fully functional yet, but what we see in the marketplace is that the players are committed. They have put their programs in place and they are issuing news loans.”

The list of players includes Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Ladder Capital Finance, Wells Fargo, UBS, Barclays Capital and Cantor Fitzgerald Real Estate, to name a few.

At least one mortgage banker is noticing deal volume on the rise. NorthMarq Capital has arranged 46 CMBS loans totaling $525 million through the first six months of 2012. That’s more than double the dollar amount for all of last year when NorthMarq arranged 30 CMBS loans totaling $214 million.

William Ross, president of Bloomington, Minnesota-based NorthMarq Capital, expects that the company will arrange $750 million to $800 million in CMBS loans in 2012, if the current pattern holds.

What accounts for NorthMarq’s uptick in volume? Ross estimates that 70 percent of the volume is tied to existing securitized loans that are about to reach maturity. Borrowers are seeking replacement financing.

A typical CMBS deal today is a 10-year loan at 75 percent loan-to-

value with a 30-year amortization, says Ross. That compares favorably with life insurance companies, which tend to be more conservative and typically offer 65 percent to 70 percent loan-to-value.

Big Hurdle Ahead

Nearly $55 billion in CMBS loans will mature in 2012, approximately 35 percent of which are five-year term, 2007 vintage debt, according to the Mortgage Industry Advisory Corp. (MIAC), which is based in New York.

In a report titled “The State of Commercial Lending,” MIAC wrote earlier this year that the vintage 2007 loans have high loan-to-value ratios and limited borrower equity. Furthermore, many of these loans are backed by assets with five-year leases signed at peak rents that will likely reset to lower market rents.

“Many will fail to refinance in the current lending environment,” warned the MIAC report. “Of the $19.7 billion in CMBS retail loans that mature this year, nearly $2.6 billion have a debt-service coverage ratio of less than 1.0. Lenders will require a substantial equity contribution to rein in loan-to-values to acceptable levels.”

As of May, the delinquency rate on CMBS loans across the five major property types (office, hotel, industrial, multifamily and retail) was 10.04 percent. The apartment sector posted the highest delinquency rate at 15.17 while retail had the lowest delinquency rate at 8.07 percent.

Fink says that CMBS special servicers are liquidating between $1 billion and $2 billion of distressed loans a month and that another $2 billion worth of loans are paying off at maturity. “The old loans are beginning to clear the system, both distressed and non-distressed, and that’s a good thing,” he notes.

On the other hand, there is approximately $60 billion of delinquent loans still in the pipeline.

The volume of distressed assets vastly exceeded anybody’s expectations or projections, says Fink. The B-piece buyers, the investors who buy the non-institutional-grade bond classes, always expected to absorb some losses from loans that soured. “Nobody expected to lose money so fast and in such high volume.”

The period from 1997 to 2007 was a bull market in fixed-income securities, emphasizes Fink, which allowed the commercial real estate community to be lulled into a sense of complacency. “You never saw interest rates spike up. You never saw huge declines in the dollar price of fixed-income securities. So, you had a lot of people who believed that there was a new paradigm, that all the financial engineering would allow you to paper over bad underwriting — but it didn’t.”

Never Again?

Borrowers who steered clear of CMBS debt prior to the Great Recession are not likely to pursue securitized financing now, says NorthMarq’s Ross. This group prefers instead to work with capital providers such as life insurance companies and banks.

Property owners who have had to work through a CMBS special servicer in order to obtain a loan modification or loan assumption almost universally “hate” the process, says Ross. “As we head into the next round of financings, if they have an alternative I think CMBS borrowers would definitely try to go with the alternative first.”

At the height of the market in the mid-2000s, CMBS lenders were focused exclusively on how many dollars they could provide at the cheapest rate, says Ross. A lot of borrowers were left in the dust because oftentimes their loans were traded two or three times to different servicers. “There is no relationship at that point,” says Ross.

NorthMarq services the majority of CMBS loans that it arranges, which enables the mortgage banker to serve as an advocate for the borrower during the life of a loan, he explains. The company has arranged more than 1,000 CMBS loans and still services more than 850 of those loans.

Ann Hambly, founder and co-CEO of Grapevine, Texas-based 1st Service Solutions, the industry’s first-ever CMBS borrower’s advocate, believes it’s highly unlikely that the securitized financing arena will ever evolve into a relationship business. Why? There are simply too many players involved, including the primary servicer, the master servicer, the special servicer, the controlling class certificate holder and the rating agencies.

The good news for CMBS lenders and investors is that borrowers tend to have short memories, says Hambly, even the ones who vow never to enter into a CMBS lending transaction again. “When money is dangled in front of them later on, and it is non-recourse at an attractive rate, I believe they will say, ‘Well, okay.’”

©2012 France Publications, Inc. Duplication

or reproduction of this article not permitted without authorization

from France Publications, Inc. For information on reprints

of this article contact Barbara

Sherer at (630) 554-6054.

|